Duncan Weston - Out of Context

Written to accompany Duncan Weston's show, I WAS HERE, at The Horse, Dublin, 05.09.24 - 20.10.24.

Is context vital in understanding an artist and their production? Art history would have us believe so, but, sometimes, said context can be so specific that it requires its own set of references. Typically, art that has been hard to define, and does not register on a Western fine art index, has been explored as ‘Outsider Art’ – a term developed from Jean Debuffet’s conception of ‘Art Brut’. Outsider Art can operate, in these terms, as a sort of catch-all, a little precarious and open to interpretation. However, in the case of DUNCAN[1] Weston, certain interpretations of the term do offer a little critical perspective on his practice. In art historian Roger Cardinal’s broad definition, Outsider Art could be characterised by ‘a distinctive repertoire of motifs and devices, which become the components of a closed architecture’.[2] This goes some way to describing DUNCAN’s world, but it is not necessarily a world that is ‘closed’ – it is very much an engaged practice that is open to those with appropriate frames of reference. Some of DUNCAN’s work may also be conceived of as ‘Autobiographical’. Yet, existing critical writings around this term deal with art that addresses universal themes - death, sex, violence. DUNCAN’s practice is outside of a fine art tradition and not attached to universality. Thus, to contextualise DUNCAN, ‘Outsider’ may be seen as insufficiently comprehensive and ‘autobiographical’ underplays the sophistication of his cultural commentary, that extends beyond the limits of his own experience. However, this experience is codified – DUCAN’s work draws expressly on his life as a writer of graffiti but is complicated by its internal contradiction – it is accessible and unintelligible, crude and sophisticated, humorous and serious, retrospective and contemporary. To grapple with these opposites necessitates an understanding of DUNCAN’s multiple identities, their genesis in graffiti culture, and his manifold divergent paths leading from a discipline, unencumbered by art history, but bound by its own traditions and idiosyncrasies.

Petro, East London, 2014. Photograph by Alex Ellison.

In other personas, DUNCAN has achieved global acclaim. As Petro TFW, he, and others, were part of a generation of graffiti artists who broke free of the tyranny of style and built a new visual lexicon that was distinctively European. Autonomy of expression in graffiti is sometimes burdened by its self-governance. An internal rule set informally presides over the conduct of writers, influencing their status in the eyes of peers. This structure must be a stricture for the compulsively creative – this was definitively the case for DUNCAN who changed his moniker from Hash to Petro in a deliberate move to reject the boundaries imposed by others. He recalls knowing that his repudiation was successful when another writer told him that they ‘used’ to like his style.[3] Petro played with the conventions of graffiti in a way that only a time served writer has the knowledge to dismantle or, perhaps, reconstruct. In new letterforms, that toyed with graffiti’s classical motifs, his arrows-out-of-arrows-out-of-arrows messed with wildstyle in a joyfully irreverent fashion that his, and graffiti’s, history both influenced and enabled. Other manipulations produced stunted arrows looking like spades, crowns upside down and tipped on their side, and a return to basic fills that referenced the earliest American pieces – when others were trying to add complexity in technique to advance the art, Petro took it backwards to drive things forwards.

A selection of paintings from ‘I WAS HERE’, The Horse, Dublin.

There is a restlessness that characterises DUNCAN’s work. His production, like many artists coming from a graffiti background, is compulsive, enshrined in a work ethic that is requisite for ‘getting up’ and achieving peer recognition on walls and on trains. At art school he was dumfounded by the lack of production – the amount of time his fellow students spent not making work – he thought it was a waste. That is not to say that DUNCAN does not make time to think critically about his output, his own context is the context. His work is out of context because the context is so specific – specific, yet generic. DUNCAN grew up in a British seaside town in the 1980s and the types of objects and experiences that he now references are his own composite of artefacts and ideas that permeated youth cultures and subcultures of the period. As he says, you could not just type in a search term to discover an entire scene, you had to graft to acquire and share knowledge, and this meant that it was nuanced and inflected by interpretation according to people and places. Certain things were ubiquitous – Raleigh Burner BMX bikes, the Sony Sports Walkman – but not every family could afford them, and they were often sourced from local dealerships, which themselves generated micro-cultural norms dependent on the owners, the staff and their preferences. It was not just objects that acquired status, brands blossomed in the brash free market capitalism of the day and brands had meaning applied to them too. DUNCAN’s paintings, rapidly rendered and imperfect versions of the artefacts they represent, play with the glossy mass-market appeal as well as affectionately recalling their value, personal and cultural, amidst sensations of loss, obsolescence and redundancy.

Ralph Lauren shop, Morecambe. Duncan Weston, 2018. Author’s photograph, 2023

DUNCAN only wears Polo Ralph Lauren. His relationship with Ralph is simple. DUNCAN LOVES RALPH, AGED 84¾. DUNCAN and hip hop have an enduring love affair with Ralph. The brand’s seemingly out-of-reach prestige in 1980s America made its products into objects of desire. Entire sub-sub-cultures emerged that manifested iconic pieces from ready-to-wear collections. In turn, this subverted brand expectations and constructed identities outside of the intended norms of the label. New York youth culture adopted the head-to-toe Polo aesthetic and mutated it in unanticipated ways that only street culture could – dressing gowns as outerwear, towels as accessories, entire tenement apartments dressed in branded goods – moving the brand from aspirational status symbol to cult icon. DUNCAN’s love transcends the brand and extends to Ralph himself. In knowingly paradoxical fashion, DUNCAN both pays homage to all things Polo and ridicules his own fascination by reproducing, in his own hand, the sharp, manicured badges, logos and monikers of the original as clumsy, thin facsimiles. DUNCAN’s homemade bootlegs make no attempt at authenticity, instead they deliberately fold mass-market appeal in on itself in tribute and in parody – a self-deprecating, ironic adulation that sustains his internal contradiction as well as creating a unique form of social commentary that is specifically out of context. DUNCAN’s Ralph project is, like his love for Ralph, extensive and enduring and includes the creation of Polo branded bicycles, cars, surfboards, cardboard jewellery and even entire shops, self-portraits in various states of undress, but always wearing Ralph. One of DUNCAN’s own justifications for his idolatry are the manifold identities that Polo enables – lifeguard, golfer, surfer, businessman, traveller – Ralph provides for every social occasion and such a melange of identity mirrors DUNCAN’s constructed reality.

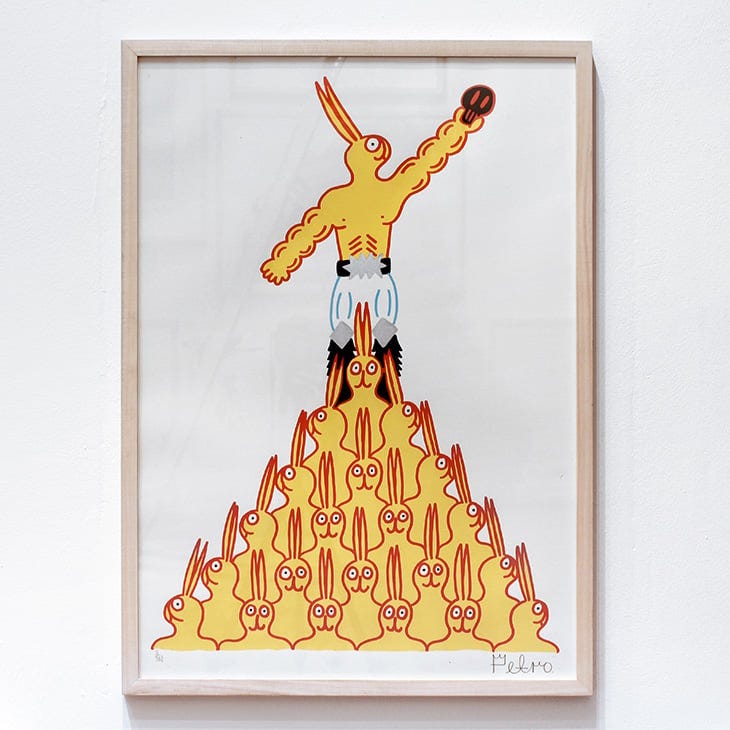

Bunt The Rabbit Pyramid. Duncan Weston, hand finished print, 2011

Graffiti creates identity. Dedicated and time-served writers build their own language of style that evolves forms, motifs and traditions into new versions. Ever since the publication of Subway Art (1984)[4], with its glossary of terms, generations of graffiti artists have stuck to a set of loose conventions with the tacit understanding that they are to be broken, toyed with, developed, whilst also acknowledged. DUNCAN’s identities almost stretch these to breaking point, but the elastic never quite gives. His ontogeny of the idea of a ‘character’ in graffiti, embodied in his creation of Bunt the Rabbit, typifies such an extrapolation. Bunt’s reproduction, though, is out of control – the rabbit cannot be contained. DUNCAN HATES BUNT. However, Bunt regularly deposits small sums of money into DUNCAN’s bank account and, despite his loathing, DUNCAN is forced to accept Bunt. At this point, identity verges on schizophrenia. In conversation DUNCAN could only discuss Bunt in the third person, a character writ large that has escaped his control and seems to be directing his own narrative beyond the hand of his creator.[5] However, whilst the rabbit has burrowed out of its cage, DUNCAN has latterly reclaimed his own name.

DUNCAN AGE 50. Author’s photograph

Weston’s deployment of DUNCAN as the most recent manifestation of his identity implies an assuredness – a self-reckoning commensurate with decades of self-awareness and, to the observer, a holistic embrace of Hash, Petro, Ralph and Bunt, in various measure. It is not a total break. Aspects of earlier practice manifestly blur in the writing of DUNCAN, most explicitly in the positive affirmation of his age at the time of writing. DUNCAN AGE 50½, and the numerative fractions that pre- and proceeded it, appeared all across London in 2023. Stating one’s age in fractions is evidently characteristic of childhood and references ubiquitous cultural norms, including that of British children’s TV show Take Hart and its Gallery segment that presented art submitted by its young viewers between 1977 and 1983. Both Petro and Ralph had their age appended to their moniker at different stages – Petro for the first time when DUNCAN was 30. This motif has been part of his practice for more than two decades and began, perhaps, at an age that society might consider too old for such youthful pursuits as graffiti, or skateboarding, or breakdancing, or any of the other cultural practices that are routinely misunderstood and misjudged as passing fads. Such ideas, of time, timeliness and obsolescence, are embodied in DUNCAN’s interventions in, or on, redundant KX100 telephone kiosks. The KX100 was introduced in 1985 and discontinued in 1996 after approximately 80,000 units were installed on the streets of Britain. Its short lifespan was in parallel to DUNCAN’s formative years and its apparent depreciation, without any of the vestiges of heritage value ascribed to its earlier cousins, the K7 and K8, speaks to lost technologies and the digitisation of society. In writing his name (in reverse from the inside), DUNCAN draws attention to the forgotten object, invisible by its visibility. His purportedly nefarious act is markedly less antisocial than some of the uses to which the micro public spaces are now put. The remnants of a more physical and fixed world, before mobile technologies, before Duncan was Hash and before Petro, Ralph or Bunt were DUNCAN, resonate with vinyl records, cassette tapes, plastic carrier bags, ink and spray paint – a collective biography of a generation, beyond its coming-of-age, approaching its historicisation and poignantly revealing its truths as DUNCAN reveals himself.

Inevitably, there are contemporary artists to whom DUNCAN might be compared, artists that could give DUNCAN’s work some context. However, here there is little utility in exploring those parallels and, in many ways, this is best left to the reader to consider. ‘Out of context’ gives us two mechanisms by which to appreciate these works: first, one might regard DUNCAN’s oeuvre as so personal and individualised that it has no comparison, or that comparisons are so stretched and incomplete that they are meaningless; secondly, in coming to understand the genesis of his reality as manifest through practice, that his work could only emerge out of (a very specific) context.

[1] I made the decision to write DUNCAN in uppercase as this is how he writes his name. In 2023 he wrote it more than 3000 times in public space in London, along with his age at the time of writing.

[2] Roger Cardinal, ‘Worlds Within’, in Felix, A. et al. (2006) Inner Worlds Outside (Madrid: Sala de Exposiciones de la Fondación "La Caixa") p.19.

[3] In conversation with the artist. London, 24 May 2024.

[4] Cooper, M. and Chalfant, H. (1984) Subway Art (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston).

[5] In conversation with the artist. London, 24 May 2024.